Common Sense excited a colonial thirst for independence. He proclaimed that “in free countries the law ought to be king.” The forty-six-page pamphlet is reputed to have sold an incredible 150,000 copies (to a population of not quite three million), giving it an even wider audience, because people passed it around or publicly read it aloud.

Paine argued for independence and liberty. In mid-January, pamphleteer Thomas Paine published Common Sense, which attacked King George III as a “royal brute” and undermined the idea of hereditary monarchy. It was time for the Continental Congress to confront the pressing question of independence. The colonies were drawing up their own constitutions and declaring their rights.

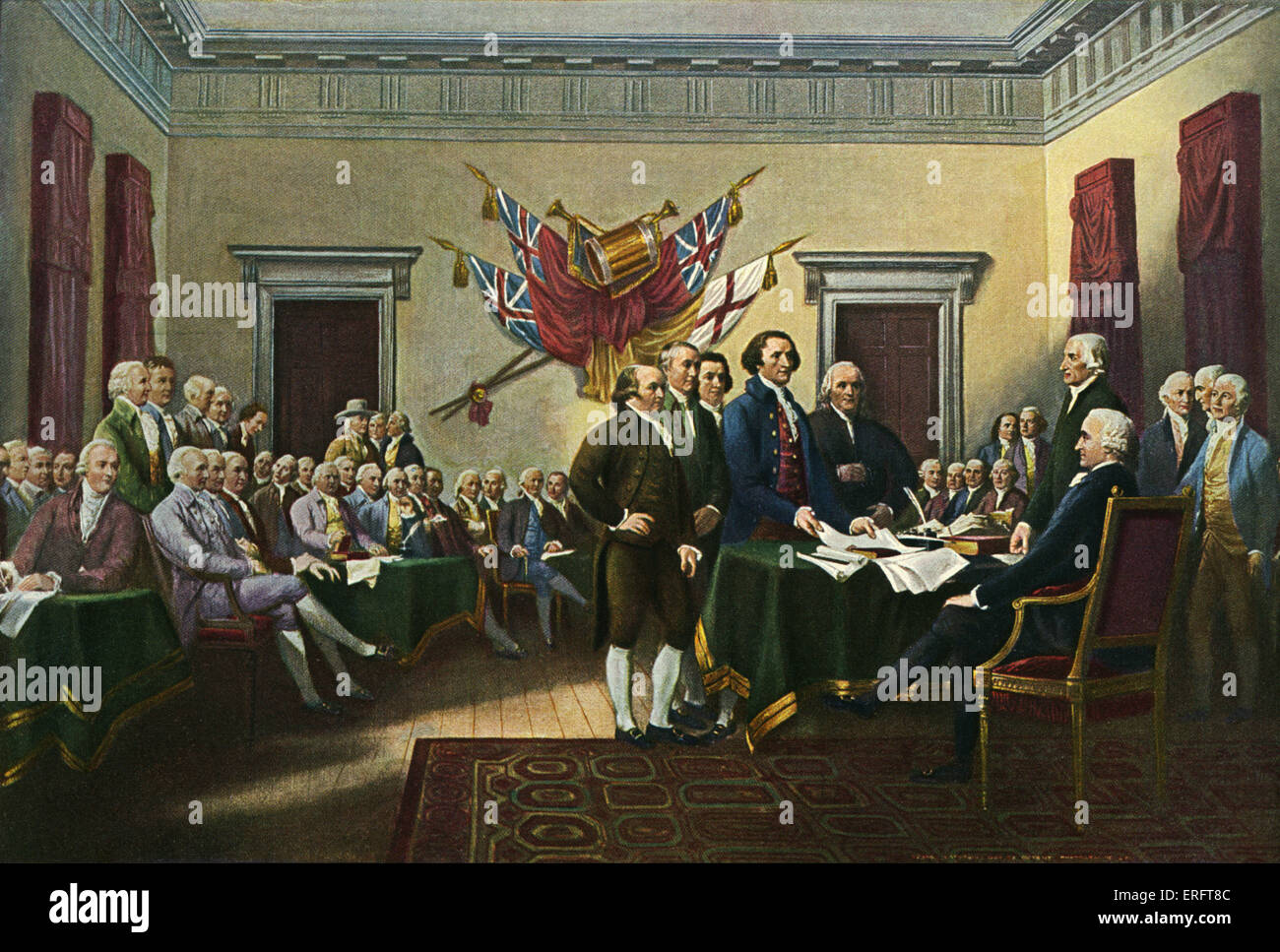

The siege of Boston had been lifted, but a larger British invasion force was preparing to attack New York. In early 1776, war raged across the colonies. Finally, she shows how by the very act of venerating the Declaration as we do-by holding it as sacrosanct, akin to holy writ-we may actually be betraying its purpose and its power.Use this Narrative with the Signing the Declaration of Independence Decision Point to give students a full picture of the declaration. Maier also reveals what happened to the Declaration after the signing and celebration: how it was largely forgotten and then revived to buttress political arguments of the nineteenth century and, most important, how Abraham Lincoln ensured its persistence as a living force in American society.

Detective-like, she discloses the origins of key ideas and phrases in the Declaration and unravels the complex story of its drafting and of the group-editing job which angered Thomas Jefferson. She lets us hear the voice of the people as revealed in the other "declarations" of 1776: the local resolutions-most of which have gone unnoticed over the past two centuries-that explained, advocated, and justified Independence and undergirded Congress's work. In Maier's hands, the Declaration of Independence is brought close to us. Maier describes the transformation of the Second Continental Congress into a national government, unlike anything that preceded or followed it, and with more authority than the colonists would ever have conceded to the British Parliament.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)